MICRO/MACRO: THE WORLD INSIDE/OUT

Part One: MICRO

Nature films are the oldest science film genre. The first examples, shown in 1903, were microscopic specimens filmed down a microscope. They immediately became established as a popular genre of science on screen.

The first part of the program focuses on 'Micro' exploration and presents a selection of footage and works from the early days of microcinematography until our decade, describing on screen how the technology and the overlap of borders between art and science brought to us a different and wider vision of the ‘Micro’ world of cells and molecules.

Part One: MICRO

Nature films are the oldest science film genre. The first examples, shown in 1903, were microscopic specimens filmed down a microscope. They immediately became established as a popular genre of science on screen.

The first part of the program focuses on 'Micro' exploration and presents a selection of footage and works from the early days of microcinematography until our decade, describing on screen how the technology and the overlap of borders between art and science brought to us a different and wider vision of the ‘Micro’ world of cells and molecules.

Photographed by the famous scientist and microscope expert, E.J. Spitta (at the time Chairman of the Microscopical Society), the film, part of a series of microphotographic studies, shows pond creatures in great detail, circulation of blood in the tail of a tadpole, movements of its digestive system and the circulation of plasma in pond weed. 'The images are of very high quality and, apart from the naming of the creatures in each shot, there is no further attempt by the filmmaker to intervene. Indeed it would be quite unnecessary, since the pictures are entirely fascinating in their own right and have lost none of their power to astound and educate.' (Bryony Dixon)

Introduced by Timothy Boon, Head of Research at Science Museum.

Secrets of Nature was the name given to the series of films made by British Instructional Films from 1922 to 1933. The pioneering series explores animal, plant and insect life, making astonishing worlds and natural processes visible through techniques of time-lapse and microcinematography. Setting themselves apart from the élite scientific discourse, these films were considered authentic amateur science brought to the cinema screen rather than popularisations of élite science.

Released in 1931, this stunning film about the life-cycle of myxomycete, or slime mould, amazes with its beautiful photography. At the time it met with criticism for its lack of scientific clarity and it has indeed proved to be inaccurate. Although the levity of the commentary was reviewed as 'unsuited either to an educated or about-to-be-educated audience' (Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1937), it has entertainment value and was instrumental at the time in capturing the audience's attention.

Secrets of Nature was the name given to the series of films made by British Instructional Films from 1922 to 1933. The pioneering series explores animal, plant and insect life, making astonishing worlds and natural processes visible through techniques of time-lapse and microcinematography. Setting themselves apart from the élite scientific discourse, these films were considered authentic amateur science brought to the cinema screen rather than popularisations of élite science.

Released in 1931, this stunning film about the life-cycle of myxomycete, or slime mould, amazes with its beautiful photography. At the time it met with criticism for its lack of scientific clarity and it has indeed proved to be inaccurate. Although the levity of the commentary was reviewed as 'unsuited either to an educated or about-to-be-educated audience' (Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1937), it has entertainment value and was instrumental at the time in capturing the audience's attention.

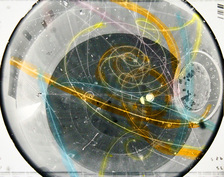

Made in 1968 for IBM, Powers of Ten is an adaptation of the 1957 book 'Cosmic View' by Kees Boeke, and was used as a teaching aid in many American schools and science museums. It was meant to appeal to an interested ten-year-old as well as to a specialist, and it had to convey a complex, theoretical way of viewing the world in a very simple manner.

Starting at a picnic by the lakeside in Chicago, the film transports us to the outer edges of the universe using a continuous zoom. The viewer is taken out from Earth to the farthest known point in space and then back through the interstitial spaces between skin cells into the nucleus of a carbon atom, while chronometers on a split screen register distance travelled at the rate of one power of ten every ten seconds. The spectator is in perspectiveless space; there is no one place where he can objectively judge another place. The strangeness of the experience is accentuated by an Elmer Bernstein score played on a Japanese synthesizer.

In 1977 Powers of Ten was re-released with the addition of a narrated text.

Starting at a picnic by the lakeside in Chicago, the film transports us to the outer edges of the universe using a continuous zoom. The viewer is taken out from Earth to the farthest known point in space and then back through the interstitial spaces between skin cells into the nucleus of a carbon atom, while chronometers on a split screen register distance travelled at the rate of one power of ten every ten seconds. The spectator is in perspectiveless space; there is no one place where he can objectively judge another place. The strangeness of the experience is accentuated by an Elmer Bernstein score played on a Japanese synthesizer.

In 1977 Powers of Ten was re-released with the addition of a narrated text.

“Metazoa” uses explorations of scale to allow otherwise-invisible water animals to occupy the same corporeal space as the viewer, radically repositioning the human in relation to the nearly-invisible water creatures. What is tiny becomes monumental, with an otherworldly grace and delicate, ephemeral color.

The subject of the video is plankton and zooplankton, primarily freshwater copepods, a bellweather species whose populations are indicators of the health of our ecosystem. In “Metazoa,” artists Lane Hall and Lisa Moline remix the archival footage of Dr. Rudi Strickler, biologist and Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s WATER Institute, and pioneer in the cinematography of copepods.

“A shift towards the macroscopic or into the microscopic suggests a multiplied multiple, a space of vast iteration, and a scale so difficult to determine, or comprehend, that the knowledge of it, or science, becomes either science fiction or allegory.” (Lane Hall)

The subject of the video is plankton and zooplankton, primarily freshwater copepods, a bellweather species whose populations are indicators of the health of our ecosystem. In “Metazoa,” artists Lane Hall and Lisa Moline remix the archival footage of Dr. Rudi Strickler, biologist and Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s WATER Institute, and pioneer in the cinematography of copepods.

“A shift towards the macroscopic or into the microscopic suggests a multiplied multiple, a space of vast iteration, and a scale so difficult to determine, or comprehend, that the knowledge of it, or science, becomes either science fiction or allegory.” (Lane Hall)

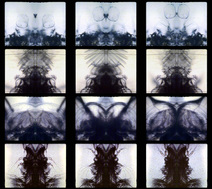

Los Angeles-based artist Jennifer West employs various unique processes to produce alchemical transformations in her film practice. Influenced by classical structuralist film and popular culture, she is known for her digitised films made by hand manipulating film celluloid to the level of performance.

This work, realised while she was an Artist in Residence at the MIT List Visual Arts Center in Cambridge Massachusetts, was the result of West's collaborative engagement with faculty and researchers in MIT's Laboratory for Nuclear Science, the Center for Materials Science and Engineering, and X-Ray Shared Experimental Facility. Made using specialized film of scientific footage of neutrino movements, inked up by hand, the work also uses substances like acid highlighters and squeaky marker pens.

* (70mm Film Frames of Neutrino Movements - shot in 15 ft Bubble Chamber at Fermilab, Experiment 564 near Chicago - dunked in liquid nitrogen, neutrino movements events with invisible ink and decoder markers and highlighters, inked up by Monica Kogler and Jwest, filmstrip from Janet Conrad, MIT Professor of Physics)

This work, realised while she was an Artist in Residence at the MIT List Visual Arts Center in Cambridge Massachusetts, was the result of West's collaborative engagement with faculty and researchers in MIT's Laboratory for Nuclear Science, the Center for Materials Science and Engineering, and X-Ray Shared Experimental Facility. Made using specialized film of scientific footage of neutrino movements, inked up by hand, the work also uses substances like acid highlighters and squeaky marker pens.

* (70mm Film Frames of Neutrino Movements - shot in 15 ft Bubble Chamber at Fermilab, Experiment 564 near Chicago - dunked in liquid nitrogen, neutrino movements events with invisible ink and decoder markers and highlighters, inked up by Monica Kogler and Jwest, filmstrip from Janet Conrad, MIT Professor of Physics)