MICRO/MACRO: THE WORLD INSIDE/OUT

Part Two: MACRO

Images of the great unknown have always fascinated scientists and artists. The first successful human space flight dates back to 1961, when the Soviet Yuri Gagarin completed one orbit around the globe. Soon after the Soviets started filming their space flights. The attempt demonstrated the fullest extent of humankind’s psychological, intellectual and technological ambition, the fulfilment of a centuries-old desire to escape the bonds of Earth and explore the universe.

Between 1957 and 1972 hundreds of spacecraft were launched into orbit around the Earth. The moving image was there to witness the union of natural and technological sublimity providing images that, several decades later, still have the power to awe. Despite the abundance of footage produced by NASA and its various Space Centres around the US since then, their too strict scientific approach doesn't allow any diversion towards a more allegorical style. The 'Macro' part of the program presents one visually overwhelming example of the outer space seen from the point of view of a great director, who creates new cinematic languages through a register that opposes the detail to the 'universal'.

Part Two: MACRO

Images of the great unknown have always fascinated scientists and artists. The first successful human space flight dates back to 1961, when the Soviet Yuri Gagarin completed one orbit around the globe. Soon after the Soviets started filming their space flights. The attempt demonstrated the fullest extent of humankind’s psychological, intellectual and technological ambition, the fulfilment of a centuries-old desire to escape the bonds of Earth and explore the universe.

Between 1957 and 1972 hundreds of spacecraft were launched into orbit around the Earth. The moving image was there to witness the union of natural and technological sublimity providing images that, several decades later, still have the power to awe. Despite the abundance of footage produced by NASA and its various Space Centres around the US since then, their too strict scientific approach doesn't allow any diversion towards a more allegorical style. The 'Macro' part of the program presents one visually overwhelming example of the outer space seen from the point of view of a great director, who creates new cinematic languages through a register that opposes the detail to the 'universal'.

|

Our Century (Mer dare)

Soviet Union | 1982 | colour | no dialogue | 35mm | 47' Director, Script: Artavazd Peleshian Photography: Laert Poghosyan, O. Savin, R. Voronov, A. Choumilov Sound: O. Polissonov Editor: Artavazd Peleshian, Aida Galstian Production Company: Erevan Studio Courtesy of: Films Sans Frontières, Paris |

Introduced by Gareth Evans, Adjunct Film Curator at Whitechapel Gallery, and James Norton, Writer and Television Producer / Director.

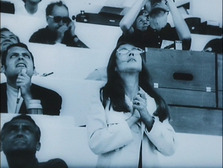

An outstanding representation of limitlessness, the film by the Armenian director and film theorist is the account of the launching of humanity into space and of the global fascination with the exploration of space by Soviets and Americans, through a complex editing system coupled with an equally complex soundtrack. There is no dialogue in the film and no narrative; however, music and sound effects play as important a role as the visual images. The film features archive of American astronauts and Peleshian's footage of Soviet cosmonauts: remarkable was the access the director had to the Soviet space programme for the filming – in particular comparing it with the impossibility of NASA doing the same for a US experimental filmmaker.

Thanks also to the footage of celebratory procession of the space heroes cheered by the mass alongside the sequences that show the immense stress the cosmonauts are put under during the test phase and in space, Peleshian is able to show with great humanity man's obsession with flight and his desire to conquer the various elements of nature.

On the border between documentary and feature, closer to avant-garde films than conventional documentaries, Peleshian's films were hardly shown in Europe because of the Soviet authorities' fear of exporting his work outside their borders.

An outstanding representation of limitlessness, the film by the Armenian director and film theorist is the account of the launching of humanity into space and of the global fascination with the exploration of space by Soviets and Americans, through a complex editing system coupled with an equally complex soundtrack. There is no dialogue in the film and no narrative; however, music and sound effects play as important a role as the visual images. The film features archive of American astronauts and Peleshian's footage of Soviet cosmonauts: remarkable was the access the director had to the Soviet space programme for the filming – in particular comparing it with the impossibility of NASA doing the same for a US experimental filmmaker.

Thanks also to the footage of celebratory procession of the space heroes cheered by the mass alongside the sequences that show the immense stress the cosmonauts are put under during the test phase and in space, Peleshian is able to show with great humanity man's obsession with flight and his desire to conquer the various elements of nature.

On the border between documentary and feature, closer to avant-garde films than conventional documentaries, Peleshian's films were hardly shown in Europe because of the Soviet authorities' fear of exporting his work outside their borders.